We’ve all had spawns that turn out all (or nearly all) female, or occasionally have more males. For betta breeders especially, figuring out how to produce mostly male offspring would be the equivalent of sliced bread for the betta hobby. Yet, despite years and years of dedicated breeding, no one knows what can really determine sex in bettas, let alone the molecular mechanism behind it. There are still wild myths in the hobby, and some even wilder scientific conjectures backed by numerous and conflicting studies!

I chose this paper because it had a relatively large sample size compared to most other studies, which gives strength to its conjectures. Previous, smaller studies had shown that spayed females gained male characteristics, and this could even occur spontaneously. In this study, Lowe and Larkin at Western Illinois University wanted to figure out whether male bettas potentially had heterogametic (XY) sex determinants, as compared to homogametic (XX) female sex determinants, like humans and many other kinds of animals. They reasoned that a sex-reversed female to male (by surgically removing the ovaries) would still be genetically homogametic (XX), and even if this sex-reversed female (called a “neomale”) was able to mate and produce offspring, it would produce all female offspring (“neomale” XX x normal female XX = females XX only).

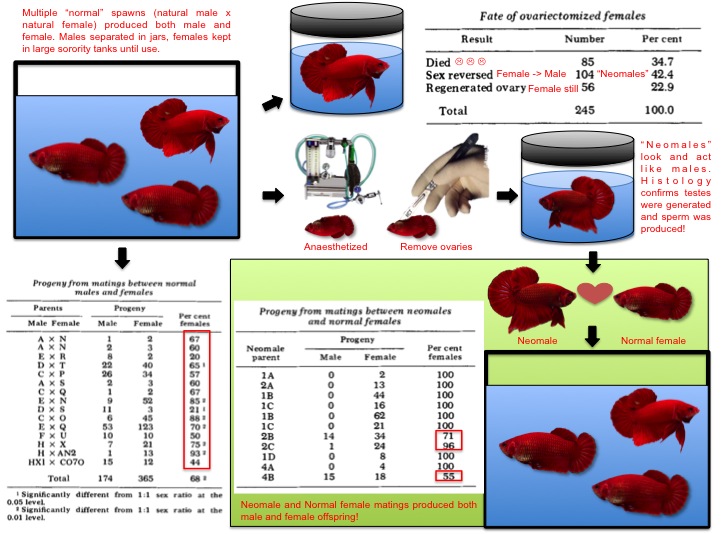

First, they bred normal males and females together to get enough stock to perform the experiments. Males were separated in quart jars while females were kept together in large tanks until use (potential caveat: some males do not show female characteristics until removed from the grow out tank!). In all, 245 characteristic females had their ovaries surgically removed. About 2/3 of the fish survived. 56 (or 22.9%) actually regenerated their ovaries and remained female. Another 104 (or 42.5%) became sex-reversed “neomales”. They gained male characteristics, and were later surgically examined and found to have generated a “testes” - an odd bladder-like structure from the cut site that was dissimilar to normal males, but nevertheless produced viable sperm.

The researchers next mated the neomales with normal females. Although not all attempts produced viable offspring, the researched were surprised that 3 out of the 11 spawning attempts that produced viable offspring were comprised of both male and female offspring! This meant that sex determination in bettas could not be based on male heterogametic (XY) and female homogametic (XX) determinants.

The authors bring up many past discussions on sex determination in their discussion, including Dr. Gene Lucas’ studies that say that mating a younger male to an older female will produce more males, as well as imperfect water conditions (observations shared by some but not all other betta researchers). Due to the production of both male and female offspring from sex-reversed females, the authors conclude that perhaps there is a brain-centered sex determinant that, once triggered as a female (the “default sex”), must be maintained as female by hormones originating from the ovaries. Once the ovaries are removed, these hormones are no longer produced, and androgens are capable of turning it into a fully functional male. The authors also speculate that sex determination occurs on the gene level rather than the chromosomal level in bettas, although one older paper reports the existence of two potential sex chromosomes that were slightly larger, this finding was unfounded in later studies). This gene level of determination may be derived from the possible mixing of several different betta “species” from different locales, which were divergent enough to have different sex determinant systems but could still interbreed. With the rampant mixing of bettas from many different regions, the sex determinant systems could have become faulty.

Lowe TH and Larkin LR. Sex reversal in Betta splendens Regan with emphasis on the problem of sex determination. J Exp Zool. 1975 Jan;191(1):25-32.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed